The George W. Adams House, located at 302 South Jefferson Street in historic downtown Lexington, Virginia, was one of my old-house listings a few years ago.

The George W. Adams House, located at 302 South Jefferson Street in historic downtown Lexington, Virginia, was one of my old-house listings a few years ago.

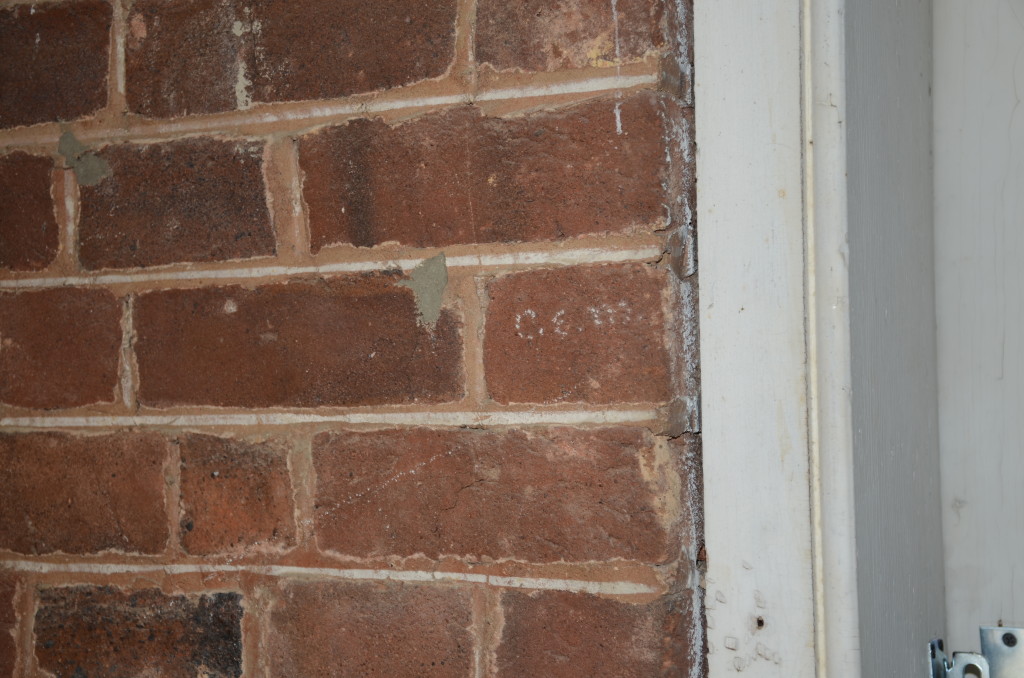

The Adams House started out as a two-story, side-passage, double-pile dwelling of braced-frame construction on a coursed limestone foundation. Adams was a merchant-artisan, specializing in tinsmithing and other metalwork. As their family grew, he and his wife Elizabeth added on to the house (ca. 1860), incorporating a large formal parlor on the first floor and a large master bedroom on the second. A rear ell was added in the late 1800s, with a kitchen and dining room on the 1st floor and 2 more rooms upstairs. The home, which retains most of its original Late-Federal and Greek Revival architectural elements and wonderful heart-of-pine floors, has been sensitively updated with modern mechanical systems, central cooling and heating, and a custom kitchen and baths. Well arranged for entertaining, it is situated on a lushly landscaped corner lot and has been featured twice on tours of Lexington during Historic Garden Week in Virginia.

Lexington is a charming small town in the Shenandoah Valley, and an easy drive to Washington DC, Charlottesville, Richmond, Charlotte, or Raleigh. Home to two institutions of higher education, Washington & Lee University and the Virginia Military Institute, Lexington is a tourist destination AND a great place to raise a family or retire. Friendly, walkable, and bike-able, it has an attractive downtown with art galleries, antique shops, boutiques, and a lively restaurant scene. The Adams House, chock-full of authentic features, is just a short stroll to everything!

Updated 2 February 2019

mid-20th century. It was owned in the late-19th and early-20th centuries by the Sheridan family, who operated a livery and stable a block away (the “Sheridan Livery Inn” on N. Main). The property is historically known as the “Back Spring Lot,” after the very bold spring in the back yard that serves as a principal source of water for Town Creek, a tributary of the Maury River. As one of downtown’s only “waterfront” properties, it offers a shady respite from the summer heat.

mid-20th century. It was owned in the late-19th and early-20th centuries by the Sheridan family, who operated a livery and stable a block away (the “Sheridan Livery Inn” on N. Main). The property is historically known as the “Back Spring Lot,” after the very bold spring in the back yard that serves as a principal source of water for Town Creek, a tributary of the Maury River. As one of downtown’s only “waterfront” properties, it offers a shady respite from the summer heat. less-residential look than other houses nearby; the two 4-panel front doors suggest it was previously used either as a duplex or as a house + shop/office. The cottage appears to have been built in at least two stages, and was last renovated in the 1990s. Original wood siding, a 1920s Craftsman-style front porch with exposed rafters and shaped rafter tails, and most of the stone perimeter foundation are some of the cottage’s intact character-defining features. The turned wooden posts are 1990s replacements of what were likely plain square posts.

less-residential look than other houses nearby; the two 4-panel front doors suggest it was previously used either as a duplex or as a house + shop/office. The cottage appears to have been built in at least two stages, and was last renovated in the 1990s. Original wood siding, a 1920s Craftsman-style front porch with exposed rafters and shaped rafter tails, and most of the stone perimeter foundation are some of the cottage’s intact character-defining features. The turned wooden posts are 1990s replacements of what were likely plain square posts.