This professional video, produced in March 2019 by Steven Shires of PixelProShop for my recently listed property at 6 Coe Place in Lexington (offered at $385,000), is just one example of the marketing tools that I use to promote properties for sale. This video doesn’t have a soundtrack added, and is just over a minute long — since research shows you have to keep marketing videos short and sweet! To enable easy viewing and sharing of the video, I first downloaded it to my YouTube channel (yes, I have a YouTube channel!), then distributed it to other platforms by embedding or sharing links to the video. It’s now accessible through our local MLS, this website, and my Facebook business page, and can be shared by you too!

I’m hoping to eventually produce and share other types of videos — interviews with local folks and businesses; walk-throughs of historic homes; on-camera tips about real estate, community, and preservation topics; and more. Soon, soon! I’ll keep you in the loop.

And for much more information about 6 Coe Place and its many distinctive features, be sure to check out the full listing at: https://www.flexmls.com/share/29AJX/6CoePlLexingtonVA24450

mid-20th century. It was owned in the late-19th and early-20th centuries by the Sheridan family, who operated a livery and stable a block away (the “Sheridan Livery Inn” on N. Main). The property is historically known as the “Back Spring Lot,” after the very bold spring in the back yard that serves as a principal source of water for Town Creek, a tributary of the Maury River. As one of downtown’s only “waterfront” properties, it offers a shady respite from the summer heat.

mid-20th century. It was owned in the late-19th and early-20th centuries by the Sheridan family, who operated a livery and stable a block away (the “Sheridan Livery Inn” on N. Main). The property is historically known as the “Back Spring Lot,” after the very bold spring in the back yard that serves as a principal source of water for Town Creek, a tributary of the Maury River. As one of downtown’s only “waterfront” properties, it offers a shady respite from the summer heat. less-residential look than other houses nearby; the two 4-panel front doors suggest it was previously used either as a duplex or as a house + shop/office. The cottage appears to have been built in at least two stages, and was last renovated in the 1990s. Original wood siding, a 1920s Craftsman-style front porch with exposed rafters and shaped rafter tails, and most of the stone perimeter foundation are some of the cottage’s intact character-defining features. The turned wooden posts are 1990s replacements of what were likely plain square posts.

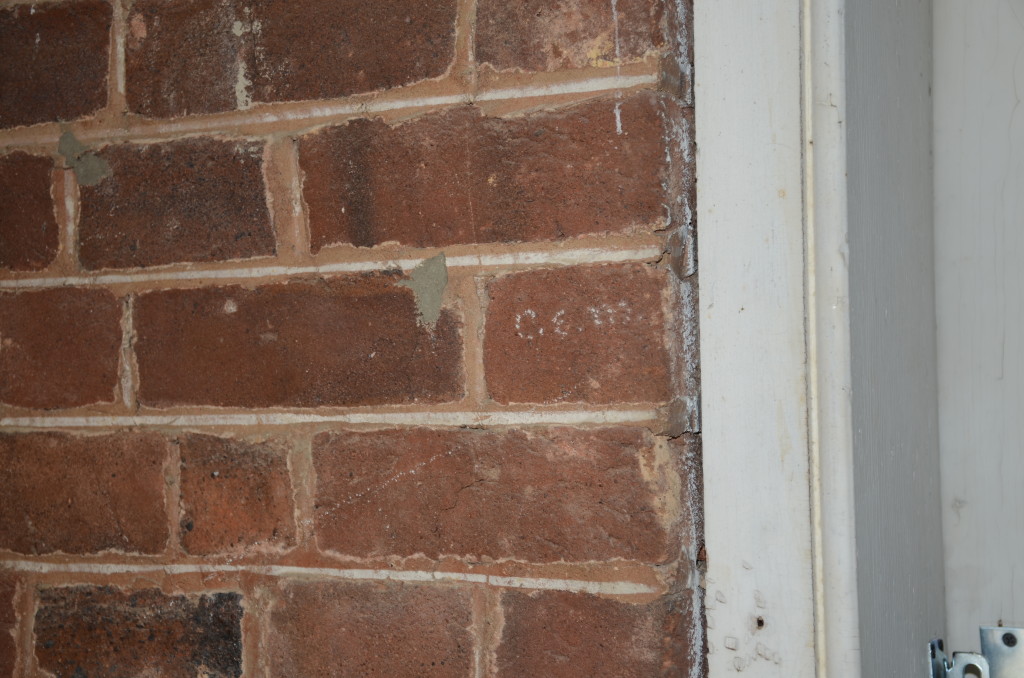

less-residential look than other houses nearby; the two 4-panel front doors suggest it was previously used either as a duplex or as a house + shop/office. The cottage appears to have been built in at least two stages, and was last renovated in the 1990s. Original wood siding, a 1920s Craftsman-style front porch with exposed rafters and shaped rafter tails, and most of the stone perimeter foundation are some of the cottage’s intact character-defining features. The turned wooden posts are 1990s replacements of what were likely plain square posts.