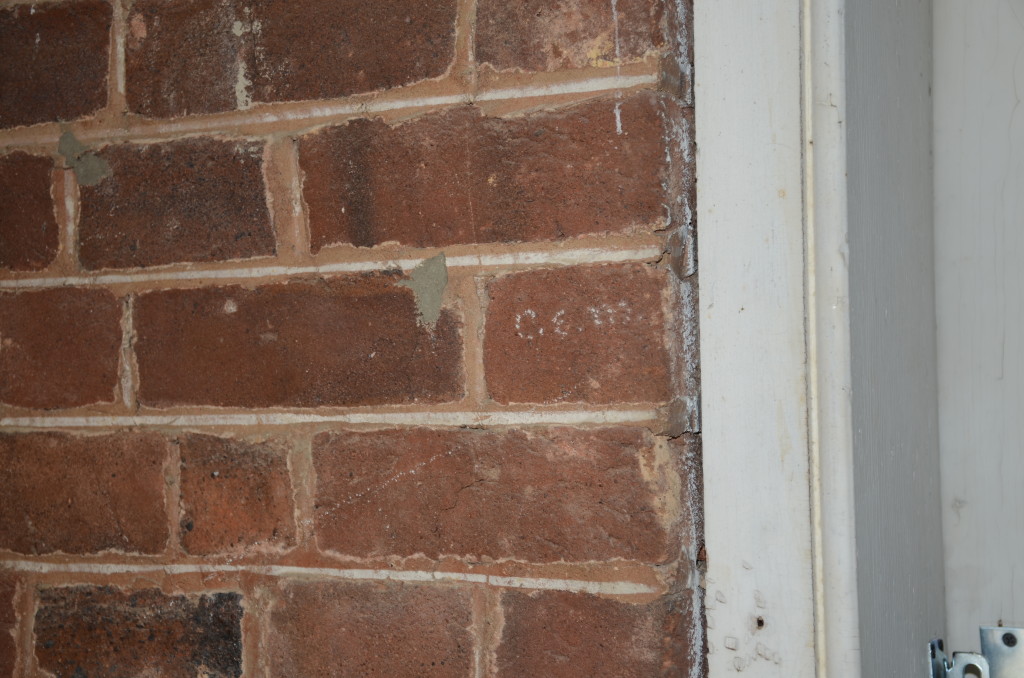

Ever heard of “penciling”? Not commonly practiced nowadays, it was once regularly used by brickmasons here in Virginia and elsewhere. Penciling refers to the technique of applying painted lines on the mortar joints of brick walls.

Bricks were once locally produced, using clay dug out of stream banks. The clay was minimally refined in pug mills, then tamped into wooden molds, then air dried, and finally baked in wood-fired kilns that had uneven temperatures. The resulting bricks were often quite irregular in size, shape, and color. With irregular bricks, even courses (rows) could only be achieved by setting the bricks into mortar joints of varying widths. In a conservative region and time period that valued regularity in masonry surfaces, brickmasons couldn’t leave those irregular bricks with their uneven mortar joints alone!

So, they pulled out their white paint, straightedges, and levels, and applied very thin stripes to every mortar joint. From a distance, especially in bright light, the stripes emulate finely struck mortar, and disguise the irregularity so typical of handcrafted brickwork.

Almost every older (pre-Civil War-era) brick building I’ve ever documented in the eastern U.S. uses penciling. Penciled joints have another virtue: alongside exterior doorways they often host signatures left by prior owners, family members, and guests. Architectural graffiti, if you will. But that’s a story for another post.